Violence, gangsters, smuggling, corrupt officials, unbearable heat, and tall men in billowing white robes all figure prominently in countless front-page news stories about the Middle East. Only last Wednesday the New York Times published a piece about the intrigue surrounding the Syrian government’s involvement in Rafik Hariri’s assassination, replete with a "masked witness," murder, and daredevil escapes. Stephen Gaghan’s film Syriana, therefore, is hardly out of step with Americans' exposure to the Middle East. It is of particular interest for those of us (myself included) who study the Middle East and have an intellectual and personal involvement in the region.

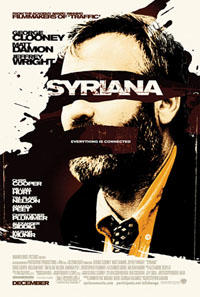

Syriana, the new film by the makers of Traffic, has much of the same attraction of their previous film. Gaghan, the writer and director of Syriana, takes on the American government with the same crusader’s conviction as in Traffic (which he also wrote). Both films are righteous engagements with the pressing issues of their time; in 2000, when Traffic was made, the War on Drugs was the toughest battle America was fighting. But part of the film’s brilliance was that drugs and the seedy world they dominated were generally ignored by the media; Traffic thus felt like an exposé. Syriana, on the other hand, takes on a subject that dominates the front page almost every day. We are up to our ears in reporting on the Middle East, which means Gaghan has to work that much harder to shock us as effectively as he did in Traffic.

The film opens with a brief sound clip of the call to prayer, in case we didn’t already know that we were in the Mysterious East. The plot—a suspenseful spin on international conspiracy—is far too complex to tackle here (the ins and outs are even more complicated than they were in Traffic). But the characters, who make up the crux of the film, suffice to give a sense of the action. We first meet Bob Barnes (George Clooney), a CIA agent on assignment in Tehran. The extra fifty pounds make Clooney look dumpy and middle aged, but his impenetrable silence turns Barnes into the most interesting character of the movie. Though we know Clooney’s winning smile from countless other flicks, he is tight-lipped and palpably uncomfortable throughout Syriana, as are most of the Americans who wind up in the region. Perhaps they should borrow a burnous from the Arabs?

Over in America, a news broadcaster’s disembodied voice informs us of the big merger between two large oil companies—and we are introduced to Bennet Holiday (Jeffrey Wright), the equally somber lawyer who’s been assigned to make sure the deal goes through. According to his boss, he’s "a lion that everyone thinks is a sheep," but we soon learn that he’s more of a jackal; he spares no one in his wily dealings on behalf of his clients. Finally there’s Bryan Woodman, a financial analyst and a do-gooder idealist perfect for Matt Damon’s babyish face. Living in Geneva, Woodman splits his time between his adorable family and a stint on a BBC-type news program.

Though Bob, Bryan, and Bennet are the major players, the film has enough characters and sub-plots to populate a small Middle Eastern country. Among them stand out Prince Nasir (Alexander Siddig), the older son of the emir whose anonymous, oil-rich kingdom in the Persian Gulf is at the crux of the conspiracy. Prince Nasir, who employs Brian as his financial advisor, plays a crucial role in the success of the oil company merger, and that is enough to get Holiday, the CIA, and Bob, involved. Finally there’s the "nice-Pakistani-boy-turned-Terrorist" sub-plot, whose rather predictable connection to the rest of the film is revealed at the very end.

"Everything is connected" (the film’s tagline) is not a new idea, but it does set high expectations for the movie. Even more so than in Traffic, the rapid-fire editing—cutting from the Middle East to DC to Geneva in less than ten minutes—gives us the sense that the world is these big players’ oyster. In the end, though, "everything" comes down to the American government, a Middle Eastern kingdom, and the giant oil companies in Texas. Although these connections are plausible, especially for lefties who have been reciting Cheney’s involvement in Halliburton since 2003, the point of a conspiracy theory movie is to present nefarious networks that we don’t know about; this was what made Traffic brilliant. At a crucial moment, the film cuts from CIA officials plotting about the Middle East in Washington to the "Oil Man of the Year" party, where Holiday and the big-wigs from the merger are celebrating their success (which, the editing tells us, they owe to the American government). Supposedly Gaghan meant this connection as a shocking revelation, but the evil, greedy faces of the Texas oil giants made them such predictable bad guys that their suspicious doings with CIA agents were not surprising in the least.

Conspiracy theories should also make us care about the effects of the plotting on the people directly involved as well as on the world as a whole. Part of the mastery of Traffic was to successfully involve the personal lives of the characters in global struggles; viewers were deeply affected by the tragic irony of the government official’s daughter who was herself addicted to cocaine. Though Gaghan tries to give us the same emotional ties in Syriana, the private subplots fall flat on the screen. We get to meet Clooney’s brattish son, and of his wife we hear "it’s amazing that two people with such high security clearances have managed to stay together." But son and wife are distant and ineffectual, and fail to make us invested in their fate.

Ultimately, though, Syriana fails because underneath all the complicated layers of conspiracy and intrigue, the basic plot is simple and uncreative. The Texas oil mongers are greedy, cackling men. In the Middle East, a story of Good-Prince/Bad-Prince pits the first-born who wants to reform his country and create a real economic infrastructure against his younger brother and the Americans who support him. And the madrasa is an equally simplistic oasis of billowing white and peaceful sunshine; to explain terrorism as merely case of material convenience seems to border on insensitivity. Maybe it’s only because I am a student of the Middle East that I know there’s more to the region than endless sand and equally tenacious American oil companies. But the worst is that Syriana is inspired by hopelessly complicated, messy events: there’s simply no excuse for making reality more predictable than it actually is.

Jesse Marglin is an AB/AM student at CMES.